trying not to die in barcelona

A Questionably Dressed Minor Croissant Influencer Writes From the Front

Friends, comrades, blood relatives, and people who still follow me after watching my slightly viral Mamma Mia 2 lookbook from 2018-

I am once again in your inbox.

The world has been increasingly shit recently on a global level and, since you asked, a little trying on a personal one too. Consequently, I have been writing a lot- but mostly things of the neurotic, circular, hand-scrawled, absolutely-must-never-see-the-light-of-day variety.

For a while now, I have been attempting to “take writing seriously,” which in my case involves submitting things to magazines and writing a novel while trying not to glance three lines back, lest I read some of my own writing and perish from shame.

(Incidentally, I’ve concluded that most writing advice is terrible BUT most advice about doing psychedelics can absolutely be applied to writing a first draft, and one should listen to that advice instead).

The main downside with deciding to “take writing seriously” was that it coincided with a time in my life when it seems I must take other things seriously too (getting a job, not getting pneumonia for the fifth consecutive time in ten months, a heartbreak, and trying to be of some use to the world as it circles the drain.)

And so here I am, crawling back to you having rudely ignored you for some time, requesting that you humour me and allow me to use this as a place to take writing unseriously- to vent, to gossip, to rant and rave, and, as in the case of this particular letter, to catch up with an old friend.

WHERE TO START !!!

My New Year's Resolution was to do one thing at a time.

Here's a quick update of the things I have been doing one at a time:

January: try not to die of pneumonia

February: become more fluent in Spanish (so that I can integrate more and create a real home in this city.)

March: try not to die of pneumonia AGAIN

April: learn to speak Catalan (as a sign of respect, and also so that the other anglophones who live here know I’m better than them.)

Wednesday 23rd April.

The 23rd of April in Catalunya is Dia de Sant Jordi. It is their version of Valentines Day,and the tradition is to give your lover a rose and/or a book. The city becomes a thick, dense labyrinth of book and rose stalls, and people stroll through the crowded streets arm in arm with their lover (or lovers- this is Barcelona after all) while pollen, love and literature fill the air.

(I am convinced I was always destined to live here: love and literature are my favourite things in the world, and pollen is the only allergy I don’t have) (touch wood).

As I jaunt down the Passeig de Gràcia in my themed red outfit (I've never encountered a bit I couldn’t overcommit to) I think a lot about Rebecca Solnit’s book Orwell’s Roses.

When Solnit discovered that George Orwell cultivated roses in his English home, she was surprised that the belligerent commie icon could have taken interest in something so “frivolous”. This becomes the starting point for a whole book of essays on the value of beauty to the human spirit and its importance and validity in the context of political struggle and justice.

Orwell fought in the Spanish Civil War and writes evocatively about his days walking the Rambla when Barcelona was Spain’s last socialist stronghold, but Solnit argues that he would have liked it covered in roses, too. It occurs to me that if Elizabeth Gilbert famously travelled to Italy, India and Indonesia to investigate (in a casual sort of way) the intersection between devotion and pleasure, Catalunya may be the place to investigate the relationship between justice and beauty. Between struggle and joy.

Monday 28th April:

I was in my Catalan class when the lights go out.

The classroom is in a very old building, with no outward facing windows. Carlo, who is Italian, asked (in Spanish, I may add, because I am attempting to learn one language I don’t know through another language I only kind of know) why in the word Barcelona the c doesn’t need a cedilla (squiggly thing that looks like “ç”) but the abbreviated name of the football team “Barça” does.

Marc, our substitute teacher, said “well, it’s the fault of your people…”.

Then the power cut out across the entire Iberian peninsula.

The rest of the language school left their classrooms and went out onto the street, but Marc was absolutely delighted to have an excuse to explain Roman-Catalan etymology, and began to write enthusiastically on the white board, which, and I cannot stress this enough, we absolutely could not see. I don’t even really know how he could see it. This carried on surreally for some time.

After class, my friend and I went searching for a matcha, surprised to find that in every cafe the power was gone too. Eventually, a message managed to get through from a girl in my class that there was no power in Spain or Portugal.

My friend and I promptly did the only sensible thing: found the last bit of cash lying around in her flat and used it to buy pre-mixed gin and tonics in a can.

I decided to ride out the power cut in her place instead of walking the one and a half hours (the metro being out of order) to my flat at the back of the city. Later I learned that my dear friends and neighbours Judit and Pau, unable to text me, had come to my flat when it got dark to rescue me.

It moved me greatly to learn that they didn’t want to leave me alone in the dark. It occurred to me that I spent much of my early twenties alone in the dark, one way or another. Perhaps being in Dublin, where I knew and loved so many people, asking any one of them to come and rescue me seemed melodramatic- but here, as an immigrant, there is a humility that comes as a great relief. I am alone, in some profound way, and that seems to make me more open, to the world and other people.

They say it takes two years to really know whether you should stay in a city. I spent a lot of the last year not quite knowing how to pierce this town.

I think the moment when the lights went out oaccross the peninsula, and someone came to rescue me, was the exact moment that I began to feel this is my home now.

Some time after midnight when we had phone service again, the group chat started to pop off. Everyone mentioned how stressed they had been and how they’d only eaten a single donut between them, trying to ration their cash in case the blackout lasted for a long time.

It was then that we realised that, in the event of an apocalypse, we were entirely likely to blow our survival money, immediately, on gin.

Wednesday 30th April:

On the 30th of April, my mum comes to visit.

(“There’s two of them!” the fine people of Barcelona scream in horror.)

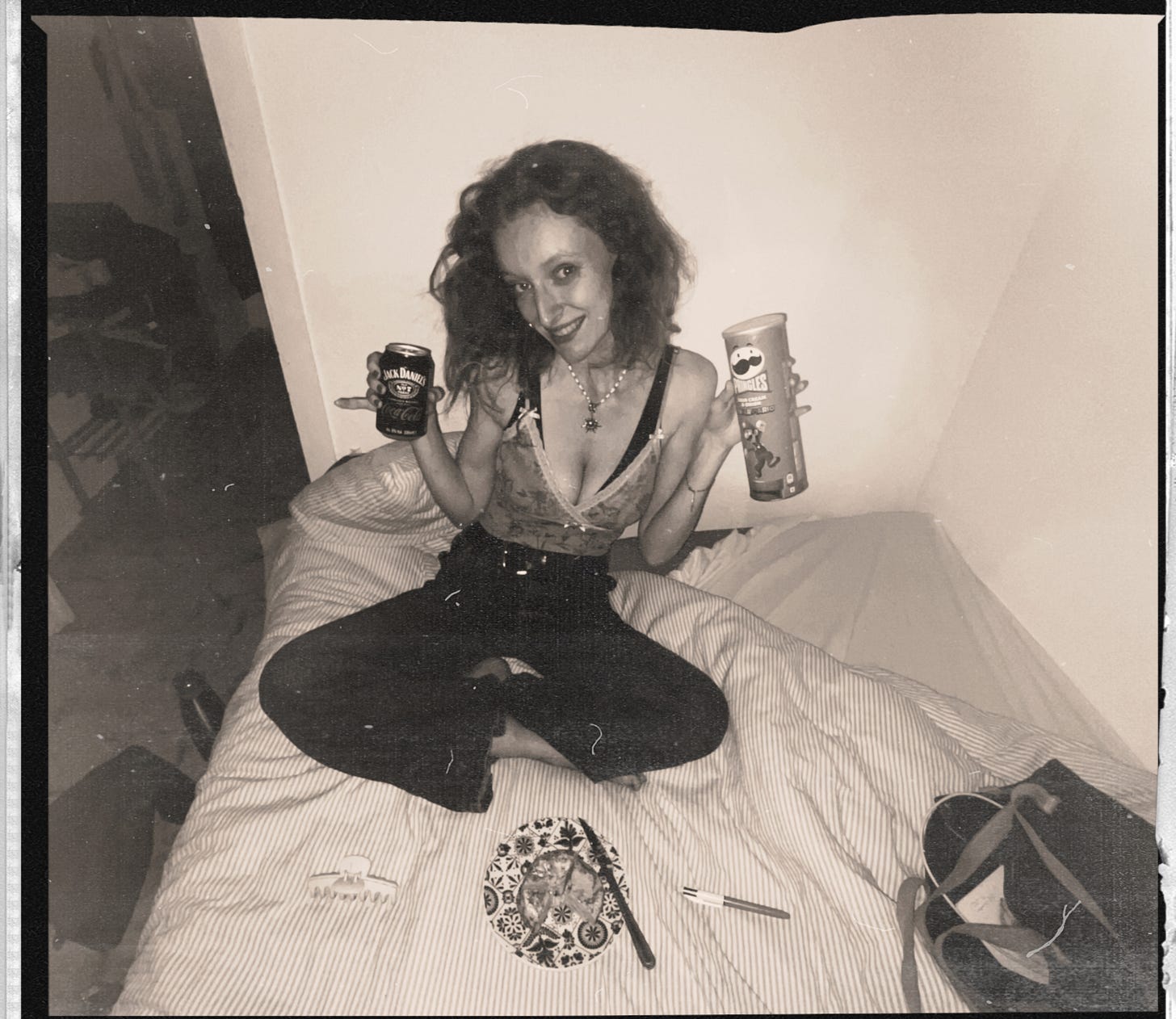

She once gave me the rather sensible advice that sometimes when your life has been a series of mounting horrors for several weeks, the only thing to do is to get extremely, gratuitously drunk, to “reset”. When the hangover lifts two days later, you have completed the purging ritual and are fresh, like a snake who has shed its skin (probably important to mention here, in case you don’t already know- we are from Ireland.)

When there has been a pervasive vibe of bravery, “let’s get through this”, and if I can just manage not to not die by spring I’ll work the rest out for several months, a girl needs an interruption of routine, a sharp vibe shift, a “reset”. I am beginning to expect that bacchanal-style bitching to your mother about everyone you’ve ever met, three vermuts deep, is more fundamentally healing than the Marie Kondo routines I dutifully clung to in my early twenties in times of crisis. We saw the city, we ate copious amounts of tapas, we watched the sunset, we laughed until we cried, and by the end I did feel like maybe some of the heaviness I have been sitting with might be beginning to shift.

God bless mothers.

God bless Vermut too, for that matter.

For a while, things have been a little too chaotic to be truly playful, but as I come out of my purifying hangover, I feel I am ready to play again.

I believe that creativity is impossible without play. I believe that healing is impossible without play. Hell, I even believe that having the stamina to fight for justice on a local or global scale requires play.

On the metro to the airport on my mum’s last day in the city, a seat becomes available and she sits in it.

“This is the first time we’ve travelled where I am the one who sits down, because you can stand” she points out.

I realise that’s true.

“Very decent of you to become able-bodied just as I’m about to get old and gaga.”

(the “gaga” comment was probably a reference to the night before, when she grated most of the cheese not onto the pasta at all but down her sleeve, and then lowered her arm, raining a considerable mountain of cheese onto the floor. We both laughed until I could not breathe and there was actual snot coming out of my nose, while she said “I don’t know how you can put up with this developmentally, people’s mothers are supposed to be dignified.”)

She tells me about a very cool art project she’s involved with involving an island off the coast of Liverpool, and then we discuss how, now that I can leave the house on a consistent basis, I have realised that when I was bedridden I had to work to regulate my emotions all the time, like the emotional body was manually operated, whereas now I can just leave the house and have my mood shifted by life itself, by the city, the world.

Which brings us, perhaps surprisingly, to Emily in Paris.

A while ago, my aunts and I got talking about Emily in Paris, and to my surprise, they began extolling her virtues. Like much of the internet, I was initially unconvinced by this questionably dressed minor croissant influencer (although, in hindsight, that may have been jealousy, since on balance, there’s nothing I’d love more than to be a questionably dressed minor croissant influencer.)

The main virtue they identified was this: no matter what happens to Emily-be it minor humiliation, major heartbreak, or potentially ruinous career setback-she only ever experiences about two and a half minutes of despair before catching sight of the Eiffel Tower. Edith Piaf swells. A travel montage begins. Once again, she forgets her troubles- because the plot is really just a vehicle for scenic travel shots, beautiful bars, glamorous outfits, campy montages, and hot French chefs.

And what I am telling you right now is that I am 27 years old in a very sexy city and I have decided to adopt the philosophy that, at least some of the time, the plot of my life is a mere vehicle for scenic travel shots, beautiful bars, glamorous outfits, campy montages and hot Catalan chefs.

If Orwell could have trenches and roses, we can have the revolution and hot Catalan chefs.

Maybe we can’t have the revolution without glamorous outfits, campy montages and hot Catalan chefs.

Ah yes, campy montages, universal symbol of the human spirit enduring.

I think I’ll end this here.

Moltes Gràcies for reading this whole bloody thing and for sticking with me all these years.

Amb molt d’amor,

F.